Quotes from Famous Modern Jewish Thinkers for Hakafot or Hoshanot Ritual

Published Monday, October 16, 2006 by Unknown.

The following is a ritual I developed for the 7 hakafot, based on the idea of the seven ushpizin (holy visitors to the Sukkah). I modified it slightly to use for the hoshanot ritual this past Saturday, while Rabbi Shoshana (my wife) used the same ritual to introduce each hakafah on Saturday night at her congregation.

Hakafot Ritual:

The Talmud says that when we read the writings of a person who has passed away, it is as if they are speaking from the grave, it is as if their lips are moving and they are again alive and speaking to us. With that teaching as our guide, for each of the seven hakafot, let us welcome in another guest, another ushpiza, another modern and holy Jewish ancestor, and read some of their words, letting them come back from the other world to speak to us for a few moments.

Albert Einstein

"A happy man is too satisfied with the present to dwell too much on the future."

"I am by heritage a Jew, by citizenship a Swiss, and by makeup a human being, and only a human being, without any special attachment to any state or national entity whatsoever."

"Whether you can observe a thing or not depends on the theory which you use. It is the theory which decides what can be observed."

"I believe in Spinoza's God, Who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God Who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind."

"Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution."

"I'm not an atheist and I don't think I can call myself a pantheist. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many different languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn't know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see a universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws, but only dimly understand these laws..."

"All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree. All these aspirations are directed toward ennobling man's life, lifting it from the sphere of mere physical existence and leading the individual towards freedom."

David Ben Gurion

• In Israel, in order to be a realist you must believe in miracles.

• If an expert says it can't be done, get another expert.

• Anyone who believes you can't change history has never tried to write his memoirs.

"We extend the hand of peace and good-neighborliness to all the States around us and to their people, and we call upon them to cooperate in mutual helpfulness with the independent Jewish nation in its Land. The State of Israel is prepared to make its contribution in a concerted effort for the advancement of the entire Middle East." Israel's Proclamation of Independence, read on May 14, 1948

"Even amidst the violent attacks launched against us for months past, we call upon the sons of the Arab people dwelling in Israel to keep the peace and to play their part in building the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its institutions, provisional and permanent." Israel's Proclamation of Independence, read on May 14, 1948

"We accepted the UN resolution, but the Arabs did not. They are preparing to make war on us. If we defeat them and capture western Galilee or territory on both sides of the road to Jerusalem, these areas will become part of the state. Why should we obligate ourselves to accept boundaries that in any case the Arabs don't accept?" David Ben-Gurion to his cabinet, May 12, 1948 [1]

"If I knew that it was possible to save all the children of Germany by transporting them to England, and only half by transferring them to the Land of Israel, I would choose the latter, for before us lies not only the numbers of these children but the historical reckoning of the people of Israel." David Ben-Gurion (Quoted on pp 855-56 in Shabtai Teveth's Ben-Gurion in a slightly different translation). [2]

"Well done, now give it back to them." David Ben-Gurion to Louis Nir, after his unit captured Hebron in the Six Day War. [3] [4]

Shalom Aleichem

A bachelor is a man who comes to work each morning from a different direction.

Gossip is nature's telephone.

Life is a dream for the wise, a game for the fool, a comedy for the rich, a tragedy for the poor.

No matter how bad things get, you got to go on living, even if it kills you.

The rich swell up with pride, the poor from hunger.

Shlomo Carlebach

"Everybody believes in God, hopefully. But do you know how much God believes in us? The world still exists. That means God believes in us; believes we can fix everything."

"If you love someone, never ignore him. When you love someone, it means you exist. Ignoring somone means, 'In my book you don't exist.' If you love somone but in their book you don't exist, that really hurts."

"Thank G-d, the religions are getting together more and more, people are getting together. And I don't mean to make gefilte fish (a Jewish delicacy which is made out of many different kinds of fish) out of religions, which sadly enough, hurts me a little bit. Some people think, let's make a gefilte fish out of all religions; everybody put a spoon in, and let's make a new soup. This is not what I am talking about. What's happening in the world is that everybody really wants to know: What do you think? What do you believe in? It doesn't mean that I have to change. If I see that somebody else has a beautiful nose, it doesn't mean that I have to take off his nose to put it on my face. He has his nose and I have my nose. I'm just looking at his nose and seeing that it is beautiful. You know, people have to realize that basically every religion is a revelation of G-d. All I can ask is, let me know a little bit of what G-d is revealing to you. But I have to do what G-d is revealing to me, because if I cut myself off from my own revelation, then again I'm not living up to G-d.We need something that G-d will reveal to all mankind, beyond everything in the world, deeper than any previous revelation, something so deep and so holy. I think the world is getting ready for it."

"If you want to become one with someone else, you can only do it with joy." Reb Shlomo Carlebach

"There is no greater simcha [joy] than to know that G-d hears our prayers. That is the greatest simcha in the world." Reb Shlomo Carlebach

"The question is not how much you love each other. The question is how much you love each other when you aren't getting along with each other." Reb Shlomo Carlebach

"The Ishbitzer Rebbe says that the greatest, highest, deepest, the most glorious G-d revelation is, when G-d lets you know that He needs you." given over by Reb Shlomo Carlebach

Rabbi Abraham Heschel

"Just to be is a blessing. Just to live is holy."

- Rabbi Abraham Heschel

"The meaning of the Sabbath is to celebrate time rather than space....Six days a week we live under the tyranny of things of space; on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to holiness in time....Eternity utters a day."

- Abraham Joshua Heschel, "The Sabbath," p.10

Shalom Asch

Not the power to remember, but its very opposite, the power to forget, is a necessary condition for our existence.

The lash may force men to physical labor; it cannot force them to spiritual creativity.

Through our soul is our contact with heaven.

Without a love of humankind there is no love of God.

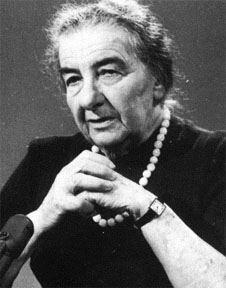

Golda Meir

I thought that a Jewish state would be free of the evils afflicting other societies: theft, murder, prostitution... But now we have them all. And that's a thing that cuts to the heart

I have faced difficult problems in the past but nothing like the one I'm faced with now in leading the country.

• Women's Liberation is just a lot of foolishness. It's the men who are discriminated against. They can't bear children. And no one's likely to do anything about that.

o Newsweek (23 October 1972)

• Let me tell you something that we Israelis have against Moses. He took us 40 years through the desert in order to bring us to the one spot in the Middle East that has no oil!

• To be or not to be is not a question of compromise. Either you be or you don't be.

o When questioned on Israel's future, The New York Times (12 December 1974)

• Pessimism is a luxury that a Jew can never allow himself.

o The Observer (29 December 1974)

It is not only a matter, I believe, of religious observance and practice. To me, being Jewish means and has always meant being proud to be part of a people that has maintained its distinct identity for more than 2,000 years, with all the pain and torment that has been inflicted upon it.

My Life (1975)

• I never did anything alone. Whatever was accomplished in this country was accomplished collectively.

o To Egyptian President Anwar el-Sadat during his unprecedented visit to Israel (21 November 1977)

• We do not rejoice in victories. We rejoice when a new kind of cotton is grown and when strawberries bloom in Israel.

o Quoted in obituaries (8 December 1978)

Zelda

On That Night

On that night,

as I sat alone in the still

courtyard,

and gazed at the stars--

I resolved in my heart--

I almost took a vow--

to devote every evening

one moment,

a single tiny moment,

to this shining beauty.

It would seem

that there is nothing easier than this,

simpler than this,

still I haven't kept up

my oath

to myself.

Why?

... On that night, when I sat alone

in the silent courtyard,

I discovered suddenly

that my house too was built on the shore,

that I live on the bank of the moon

and the constellations,

on the bank of sunrises and sunsets.

Anne Frank

Everyone has inside of him a piece of good news. The good news is that you don't know how great you can be! How much you can love! What you can accomplish! And what your potential is!

• God never deserted our people. Right through the ages there were Jews. Through the ages they suffered, but it also made us strong.

How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before beginning to improve the world.

There is an urge and rage in people to destroy, to kill, to murder, and until all mankind, without exception, undergoes a great change, wars will be waged, everything that has been built up, cultivated and grown, will be destroyed and disfigured, after which mankind will have to begin all over again.

• I don't think of all the misery, but of all the beauty that still remains.

• It's difficult in times like these: ideals, dreams and cherished hopes rise within us, only to be crushed by grim reality. It's a wonder I haven't abandoned all my ideals, they seem so absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart. I simply can't build my hopes on a foundation of confusion, misery, and death...and yet...I think...this cruelty will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again.

• Laziness may appear attractive but work gives satisfaction.

• Parents can only give good advice or put them on the right paths, but the final forming of a person's character lies in their own hands.

• The only way to truly know a person is to argue with them. For when they argue in full swing, then they reveal their true character.

• The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere where they can be quiet, alone with the heavens, nature and God. Because only then does one feel that all is as it should be and that God wishes to see people happy, amidst the simple beauty of nature. As long as this exists, and it certainly always will, I know that then there will always be comfort for every sorrow, whatever the circumstances may be. And I firmly believe that nature brings solace in all troubles.

Hanna Arendt

• Man cannot be free if he does not know that he is subject to necessity, because his freedom is always won in his never wholly successful attempts to liberate himself from necessity.

o The Human Condition (1958), part 3, chapter 16

• What makes it so plausible to assume that hypocrisy is the vice of vices is that integrity can indeed exist under the cover of all other vices except this one. Only crime and the criminal, it is true, confront us with the perplexity of radical evil; but only the hypocrite is really rotten to the core.

o On Revolution (1963), ch. 2

• No punishment has ever possessed enough power of deterrence to prevent the commission of crimes. On the contrary, whatever the punishment, once a specific crime has appeared for the first time, its reappearance is more likely than its initial emergence could ever have been.

o Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963): Epilogue

The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution.

The New Yorker, 12 September 1970

The chief reason warfare is still with us is neither a secret death-wish of the human species, nor an irrepressible instinct of aggression, nor, finally and more plausibly, the serious economic and social dangers inherent in disarmament, but the simple fact that no substitute for this final arbiter in international affairs has yet appeared on the political scene.

Crises of the Republic (1969): "On Violence"

• Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. Violence appears where power is in jeopardy, but left to its own course it ends in power's disappearance.

o Crises of the Republic (1969): "On Violence"

The defiance of established authority, religious and secular, social and political, as a world-wide phenomenon may well one day be accounted the outstanding event of the last decade.

Crises of the Republic (1969): "Civil Disobedience"

The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

The Life of the Mind (1978): "Thinking"

Emma Goldman

• The God idea is growing more impersonal and nebulous in proportion as the human mind is learning to understand natural phenomena and in the degree that science progressively correlates human and social events.

• The free expression of the hopes and aspirations of a people is the greatest and only safety in a sane society.

o If I can't dance, it's not my revolution!

• No sacrifice is lost for a great ideal! (p. 135)

o I do not believe in God, because I believe in man. Whatever his mistakes, man has for thousands of years past been working to undo the botched job your God has made.

Crime is naught but misdirected energy. So long as every institution of today, economic, political, social, and moral, conspires to misdirect human energy into wrong channels; so long as most people are out of place doing the things they hate to do, living a life they loathe to live, crime will be inevitable, and all the laws on the statutes can only increase, but never do away with, crime.

Anarchism, What it Really Stands For (1910) [1]

• Someone has said that it requires less mental effort to condemn than to think.

o Anarchism: What It Really Stands For

• The average mind is slow in grasping a truth, but when the most thoroughly organized, centralized institution, maintained at an excessive national expense, has proven a complete social failure, the dullest must begin to question its right to exist. The time is past when we can be content with our social fabric merely because it is "ordained by divine right," or by the majesty of the law.

o Prisons: A Social Crime and Failure

Emma Lazarus

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles.

The New Colossus

• Alas! we wake: one scene alone remains, --

The exiles by the streams of Babylon.

o In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport

• The funeral and the marriage, now, alas!

We know not which is sadder to recall;

o In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport

Information on Shmini Atzeret from Rabbi Ben

Published by Unknown. Below is the information I used to provide my talk last Shabbat on Shmini Atzeret. If you would like to learn more about this intriguing holiday read on!

Below is the information I used to provide my talk last Shabbat on Shmini Atzeret. If you would like to learn more about this intriguing holiday read on!The Eighth Day of Solemn Assembly & the Rejoicing of the Law

Note: In Israel, these two festivals are celebrated together on the same day.

Shmini Atzeret - Different from Sukkot

Although perceived as the last day of the festival of the Sukkot, the "Feast of the Eighth Day" is in reality unconnected with the previous days, especially in agricultural and national conceptions. In contrast to the abundance of sacrifices that used to be offered up during the festival of Sukkot in Temple times, only one sacrifice was made on this festival.

Also, we can detect original prayers and psalms in the liturgy of Shmini Atzeret which traditionally marked it off from Sukkot.

On the other hand, the one behest of the Bible which stood out on the Eighth day was the command, yet again, to be joyful.

The celebration would now be in the home and not in the Sukkah. The festival thus marks a change in emphasis - from the universalism of Sukkot (as represented by the 70 sacrifices for the nations of the world) to the intimacy of a people and its Maker: "Now bring a sacrifice for yourselves" - Zohar.

Significance

Although the word Atzeret means "Assembly" it also has the meaning of holding back. And our sages were unable to find any special purpose to the festival of the Eighth day except as expressed in the following parable:

God is like a king who invites all his children to a feast to last for just so many days; when the time comes for them to depart, He says to them: "My children, I have a request to make of you. Stay yet another day; I hate to see you go."

That the sages saw Shemini Atzeret in terms of "sweet sorrow", is typical of their attitude to all festival days. These were days of joy, not of burden; of pleasure, not only of duty, in which they were guests in the palace of the Lord.

The Prayer for Rain

On Shmini Atzeret, (also Simhat Torah in Israel,) a prayer for rain is invoked in the Synagogue.

It appears at a stage in the festivities after the harvest was brought in and after the season of sitting in the Sukkah, both of which would be affected by untimely rains.

The prayer itself was composed by Rabbi Eleazar Ha-Kallir who also is the author of the Hoshanot that are said throughout Sukkot and who was one of the greatest and certainly most prolific of the liturgical poets. He composed piyyutim, liturgical poems or poetical prayers for all the festivals and they were widely adopted into the prayer services. Ha-Kallir lived in the Land of Israel probably towards the end of the sixth century, although some scholars place him in a later period.

The season chosen for the recitation of this prayer for rain reflects the weather conditions and agricultural needs as they exist in the Land of Israel.

Even though this prayer at this time of the year may not be relevant for Jews scattered to other parts of the globe, their continued recitation of this and similar prayers serves to heighten their consciousness of the Holy Land and to help them maintain their spiritual bond with the Land of Israel.

The central theme running through the prayer for rain is ZEKHUT AVOT, "the merit of the fathers." The Jewish people plead for rain and sustenance, claiming not their own worthiness but for the righteousness of their saintly ancestors, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. This theme also runs through all of the prayers for forgiveness and atonement on Yom Kippur.

Simhat Torah

Simhat TorahSometime after the 11th century, Shemini Atzeret also came to be known as Simhat Torah, "Rejoicing of the Torah." In the Diaspora, this name was applied only to the second day of Shemini Atzeret.

The Basis

Although the name was not known in the talmudic period, the practice of reading the final portion of the Torah, Deuteronomy 33-34, on this day was set by the Talmud. From this practice, there gradually grew a tradition of a special, joyous celebration to mark that completion.

The basis for such a celebration is found in the Midrash which described Solomon as having made a special feast after he was granted wisdom. Said Rabbi Eleazar:

"From this we deduce that we make a feast to mark the conclusion of the Torah, for when God told Solomon, 'I have given you a wise and understanding heart like none who came before you or after you . . .' and he immediately made a feast for all his servants to celebrate the event, it is only proper to make a feast and celebrate when finishing the Torah."

The Development

While the tradition of added merriment on this last day of the holiday in honor of completing the Torah began during the ninth and tenth centuries of the common era, at the time of the Geonim, the name Simhat Torah came into use even later.

The custom of reading of the last portion of the Torah was set by the Talmud, but that of reading of the first chapter of Genesis was not introduced on Simhat Torah until sometime after the 12th century. The reasons given for this additional reading were:

1) to indicate that "just as we were privileged to witness its completion, so shall we be privileged to witness its beginning" and

2) to prevent Satan from accusing Israel that they were happy to finish the Torah (in the sense of getting it over with) and did not care to continue to read it.

Initially it was the custom for the same person who completed Deuteronomy to read the Genesis portion from memory without using a scroll, on account of the general rule that "two scrolls are not taken out for one reader."

Eventually the practice developed of calling two different persons, one for the reading of the last portion of Deuteronomy and one for the first portion of Genesis, and two different scrolls began to be used.

The Honor

Each of these ALIYOT (callings to the Torah) came to be regarded as great honors.

The people so honored were called HATANIM, Bridegrooms (of the Law). The one who presided over the completion of Deuteronomy was called HATAN TORAH, Bridegroom of the Torah. The one who presided over the beginning of Genesis was called HATAN BERESHIT, the Bridegroom of Genesis.

It became customary for the men so honored to sponsor a festive meal later in the day. In our own day, those so honored usually sponsor a special Kiddush following services.

Hakkafot

The ritual custom most closely identified with Simhat Torah is that of the hakkafot. Hakkafot is the term used to designate ceremonial processional circuits, whether in the synagogue or elsewhere.

On Simhat Torah, all the Torah scrolls are removed from the Ark, and carried around the central platform in seven hakkafot. This takes place during the evening service and also before the readings from the two Torah scrolls (described above) during the morning service. Hasidic practice in the Diaspora is to conduct hakkafot also at the evening service of the first day of Shemini Atzeret, as in Israel.

Origins

Although the custom of hakkafot on Simhat Torah is of rather late origin, dating from about the last third of the 16th century (in the city of Safed), the practice of hakkafot goes back much further.

Processional circuits are first mentioned in the Bible, as a build-up to the downfall of the walls of Jericho. There were seven circuits around Jericho; once a day for six days, and seven times on the seventh day.

The lulav (and aravot too) were carried around the Temple altar during the seven days of Sukkot; once a day during the first six days, and seven times on the seventh day (see above). From there developed the custom of hakkafot around the synagogue with the lulav and the etrog.

At traditional Jewish wedding ceremonies the custom of hakkafot is still to be seen in the circling by the bride around the bridegroom at the very start of the ceremony, usually seven circuits.

Three such circuits (Persian custom) can be said to symbolize the three-part passage from the Prophets which describes Israel's relationship to God in terms of an idyllic betrothal and marriage:

I will betroth you unto me forever;

I will betroth you unto me in righteousness and judgment, in loving-kindness and mercy;

I will betroth you unto me in faithfulness and you shall know the Lord.

(see also weekday morning prayer for putting on tefillin).

Song and Circuit Dancing

In addition to the prescribed passages, it is commonplace for the congregation to join in the singing of many additional songs, generally verses from the Bible or the prayerbook that have been put to music.

It is also the practice in the more traditional congregations for the worshippers to join a circle and dance in between each circuit. Those holding Torah scrolls also join the dancing.

In the yeshivot, the schools of higher Jewish learning, and in those congregations where traditional youth predominates, the singing and dancing that accompany the hakkafot can last for many hours. It is sometimes even carried outdoors. The whirling bodies and the stomping feet, perhaps a performance of acrobatic feats by someone inside the dancing circle, all accompanied by continuous song, provide a scene of ecstatic joy.

Small children are generally given decorative flags or miniature scrolls and they too follow the Torah scrolls in the processions.

Special Blessing for Children

In addition to involving the children in the Torah procession, it also became customary to include them in the Torah reading which follows.

Although a child under the age of thirteen is not generally called to the Torah for an aliyah, on Simhat Torah there developed the custom of kol ha-ne'arim which means "all the children," and refers to the fact that all of the children in the congregation are called up collectively and given a joint aliyah.

A tallit is spread over the heads of the entire group and the blessings, led by one adult, are recited.

At the conclusion of the reading, the congregation invokes Jacob's blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh as a special blessing for the children.

"May the Angel who has redeemed me from all harm, bless the children. In them may my name be recalled, and the names of my fathers, Abraham and Isaac . . ."

Simhat Torah in Israel

In Jerusalem, it is now customary on Simchat Torah morning for some congregations to join together in a mass dancing procession through the city to the Western Wall.

Led by scrolls of the Torah carried under the canopies, literally thousands of people, young and old, eight and ten abreast, dance and sing their way to the Western Wall in a procession that stretches for as far as the eye can see.

The original custom of holding the hakkafot at the conclusion of Simhat Torah inspired the custom in Israel of carrying the Simhat Torah celebration also into the night after the holiday. Public gatherings with bands and music featuring hakkafot and singing and dancing are then held.

In one public square of Jerusalem, it is customary for the Chief Rabbis and high government officials to participate. At that celebration there is featured the varied practices of the different Jewish communities: Hasidic, Yemenite, Bukharan, native Israeli, etc. A different group is responsible for each of the hakkafot, doing it in their respective traditional dress and with their traditional melodies.

At one time, this was also the moment for identification with Soviet Jewry, who held their own extensive celebrations in Moscow, Leningrad and other major towns on this date.

Hakkafot also take place at Israel's army bases, and even men near frontline positions have been known to participate in them during quiet periods. In the midst of the Yom Kippur War which lasted till after Sukkot, television crews recorded scenes of the Chief Rabbi of Israel, Shlomo Goren, visiting forward army bases, having brought with him a small Torah scroll, and of men joining him in some traditional dancing with the Torah.

- Hide quoted text -

Bringing The Cycle To An End

The end of the fall holiday season looks forward to redemption.

By Michael Strassfeld

Reprinted with permission from The Jewish Holidays: A Guide and Commentary (Harper and Row).

We have seen that there are two kinds of time--historical time, which marks progress, and cyclic time, which is marked by recurring patterns. Historical time is centered in the High Holiday festival cycle. Cyclic time is found in the three pilgrimage festivals. Sukkot is the end of the pilgrimage cycle, and yet, by its placement in the year, also brings to a close the High Holiday cycle. Seemingly, then, Sukkot comes at the end of both kinds of time.

Redemption is Sukkot's theme and as such it answers the great question of Yom Kippur: Are we forgiven? Yet Sukkot only promises redemption and thus reflects an underlying uncertainty that bespeaks a cruel reality. Since redemption still has not come, Sukkot continues to signify our status as wanderers lost in the desert.

Despite Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, most of us are still far away from each other and the Other. Despite the liberation of Pesach and the revelation of Shavuot, we do not end the pilgrimage festival cycle by entering the Promised land; we are left wandering as the Promised Land eludes our grasp. On Sukkot, we rejoice with our lulav and etrog, imbued with a sense of relief, security, and joy now that the penitential days are over, and yet we sit in our sukkot, those temporary dwellings, open to the winds of time--both kinds of time.

If Sukkot brings both cycles to a close, it does so by looking toward the end of time and the final redemption. Sukkot's haftarah [prophetic reading], from the prophet Zechariah [chapter 14:1-21], describes how in the future all the nations will go up to Jerusalem in peace to worship the Lord on the holiday of Sukkot.

To understand Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, we must go back a bit. The seven days of Passover are followed by the 49 (7 X 7) of the omer, climaxing with the 50th day of Shavuot. Thus liberation is linked with revelation and the giving of the Torah. The experience of receiving the Torah is awesome. It is characterized by boundaries set around the mountain and a sound so terrible that the people flee. The mountain looms threateningly over their heads. There are no joyful outbursts at Sinai, only fear and anticipation. The experience concludes with the people's acceptance of the Torah and the Covenant.

Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are preceded by Sukkot, again seven days followed by one day, but here there is no intervening period as there is between Pesach and Shavuot. Shemini Atzeret is the eighth day--that is, the day after seven. Seven, being a perfect number in Judaism, signifies a complete unit of time--each week ends with the seventh day, Shabbat. Thus, the eighth day is the day after time. It is the end of both kinds of time. It is thus not just the promise of redemption but the actual moment of it. God said, "Remain with me [atzeret] an extra day," a time beyond time.

Shemini Atzeret is a taste of the messianic, of the time when Torah, the Holy One, and Israel will be one. This comes to a climax with Simchat Torah. Instead of circling around the Torah scrolls as we did on Sukkot, during hoshanot we circle with the Torah scrolls. We take the connecting link between us and God--our ketubah [marriage contract], as it were--and circle around an apparently; empty space that is filled with the One who fills everything.

Simchat Torah celebrates a Torah of joy, a Torah without restrictions or sense of burden. We circle God seven times with the Torah and then no more. There is no eighth circling. We read from the last portion of the Torah just before we enter the promised land, but leave the last few verses unread--the Torah unfinished. It is a magical moment when all that exists are God and Torah and ourselves. We throw ourselves into endless circles of dancing and become time lost.

But this moment must pass. Time does continue, and therefore the unity is broken. The sun rises and historical time, briefly halted, begins again. Cyclic time begins as well, for we start again the Torah reading cycle. There is no end to Torah; after Deuteronomy, we immediately begin Genesis as part of a constantly renewing cycle.

We also read the first chapter of the Book of Joshua, which shows that even after the Torah there is still something else. The Torah did not end last night. There is more to hear, for not only does the Torah cycle begin again, the Torah itself enters historical time beginning with the Book of Joshua.

Then, too, the Book of Joshua is the fulfillment of the dream of entering the Promised Land. It tells us that last night was no illusion, that the moment of redemption is always at hand.

Michael Strassfeld is rabbi at the Society for the Advancement of Judaism in New York City. He is the founding chairperson of the National Havurah Committee and is the author, editor or co-editor of numerous articles and books, including The Jewish Catalogue series.

God's Nostalgia

Rejoicing to prove a point

By Rabbi Irving Greenberg

Reprinted with the author's permission from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays (Touchstone ).

When the seven days of Sukkot end, the Bible decrees yet another holiday, the Eighth Day of Assembly. The Rabbis interpreted this as an encore. After the High Holy Days, after the intense seven days of Sukkot and pilgrimage, the Jewish people are about to leave, to scatter and return to their homes.

God grows nostalgic, as it were, and pensive. The people of Israel will not come together again in such numbers until Passover six months hence. God will soon miss the sounds of music and pleasure and the unity of the people. The Torah decreed, therefore, an eighth day of assembly, a final feast/holy day. On this day Jews leave the sukkah to resume enjoying the comfort of solid, well built, well-insulated homes. The lulav and etrog are put aside; this day, Shemini Atzeret, is a reprise of the celebration of Sukkot but without any of the rituals. The message is that all the rituals and symbolic language are important but ultimately they remain just symbols.

Over the course of history this day has evolved into the day of the Rejoicing of the Torah (Simchat Torah). In Israel [and in many liberal congregations], Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are celebrated together on one day. In the Diaspora where an extra holy day is added (making a ninth day), Shemini Atzeret is followed by Simchat Torah on the ninth day. The rejoicing makes a statement. Whatever the law denies to Jews, whatever suffering the people have undergone for upholding the covenant cannot obscure the basic truth: The Torah affirms and enriches life. At the end of this week of fulfillment, on this day of delight all the scrolls are taken out of the ark, and the Torah becomes the focus of rejoicing.

Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg is the president of Jewish Life Network and founding president of CLAL--the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership. He is also the author of numerous books and articles dealing with Jewish theology and religion.

The Morning Service

Ending -- and beginning -- the Torah cycle

By Rabbi Ronald H. Isaacs

Excerpted from Every Person's Guide to Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret, and Simchat Torah. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. Copyright 2000 Jason Aronson, Inc.

The morning service is the usual holiday one, with its own Amidah and the Hallel Psalms of Praise. After Hallel, the hakafot processionals follow as on the night before. After the hakafot, all the Torah scrolls--except three--are returned to the Ark. Three scrolls are needed, one for the reading of the sidra [portion]of Vezot HaBeracha [end of Deuteronomy],the second for the reading of the first chapter of the Book of Genesis, and the third for the concluding maftir portion [omitted in some liberal congregations].

Since the custom is for everyone to be honored with an aliyah on Simchat Torah, the section from Vezot HaBeracha is read over and over again. To facilitate this, large congregations will divide into smaller groups, each with its own Torah. Other congregations will call up more than one person at a time.

Usually the last aliyah is a special one, reserved for kol ha-ne'arim--"allthe children." Only this one time during the year, children who have not reached the age of Bar or Bat Mitzvah are given a Torah honor. A large tallit [prayer shawl]is spread like a canopy over their heads as they say the blessings along with an adult who accompanies them.

The last part of the Torah reading from the first Torah scroll is the reading of the last verses of the Book of Deuteronomy (33:27-34:12) The person honored with this aliyah is called the chatan Torah--"groomof the Torah." In synagogues that are egalitarian and offer equal participation to women, a woman may be given this honor, called the kallat HaTorah--"brideof the Torah." This person is generally a distinguished member of the congregation, and is called up to the Torah with a special piyyut [liturgical poem]in praise of the Torah. The following is a suggested text for the calling up of the chatan Torah:

"Requesting permission of God, mighty, awesome, and revered, and requesting permission of the Torah, our precious treasure which we celebrate, I lift up my voice in song with gratitude in praise of the One Who dwells in sublime light, Who has granted us life and sustained us with faith's purity, Who has allowed us to reach this day of rejoicing in the Torah which grants honor and splendor, life and security, which brings joy to the heart and light to the eyes, and happiness to us when we in- corporate its values which we cherish. The Torah grants long days and strength to those who love and observe it, heeding its warnings absorbed in it with reverence and love without setting prior conditions. May it be the will of the Almighty to grant life, lovingkindness, and a crown of blessings in abundance to [insert name] who has been chosen for this reading of the Torah at its conclusion."

After this aliyah, the beginning of Genesis (1:1-2:3) is, read from the second Torah scroll. The person honored with this aliyah is called the chatan bereshit--"groomof Genesis" (or kallat Bereshit --"brideof Genesis"). Again, a special piyyutis recited. As the first chapter of Genesis is read, the congregation recites for each day of creation veyehi erev veyehi voker--"therewas evening and there was morning"--which is repeated by the Torah reader. It is customary in many places to spread a tallit like a canopy over the chatan Torah and chatan Bereshit.

The lifting of the second Torah scroll is done in a special fashion. The person crosses his or her hands so that the scroll, when lifted, is reversed (i.e., the Hebrew script is facing the congregation). [This is not done at all congregations.] This is done to symbolize turning the Torah back to its beginning--to Genesis.

The third scroll is the maftir scroll, from which the concluding Torah portion of Numbers 29:35-30:1 is read. This is followed by the chanting of the Simchat Torah Haftarah, from the first chapter of the Book of Joshua.

The Musaf Additional Service for Simchat Torah is the usual festival one, except that the joyous mood is maintained by the ingenuity of the reader. Latitude is given to merriment, and some synagogues allow tasteful "fooling around" in order to heighten the great joy of the day. Simchat Torah thus gives expression to the unbreakable chain--the Torah--that links past and future generations. In that chain lies the secret of the eternal validity of the Jewish people.

Encyclopedia Judaica Entry on Simhat Torah:

On this festival, the annual reading of the Torah scroll is completed and immediately begun again. Simhat Torah, as a separate festival, was not known during the talmudic period. In designating the haftarah for this day, the Talmud refers to it simply as the second day of Shemini Azeret (Meg. 31a). Similarly it is termed Shemini Azeret in the prayers and the Kiddush recited on this day. Its unique celebrations began to develop during the geonic period when the one-year cycle for the reading of the Torah (as opposed to the triennial cycle) gained wide acceptance.

The Talmud already specified the conclusion of the Torah as the portion for this day (i.e., Deut. 33–34; see Meg. 31a). The assignment of a new haftarah, Joshua, is mentioned in a ninth-century prayer book (Seder Rav Amram, 1 (Warsaw, 1865), 52a, but see Tos. to Meg. 31a). Later it also became customary to begin to read the Book of Genesis again on Simhat Torah. This was done in order "to refute Satan" who might otherwise have claimed that the Jews were happy only to have finished the Torah, but were unwilling to begin anew (Tur, OH 669; cf. Sif. Deut. 33).

During the celebrations, as they continue to be observed by Orthodox and Conservative congregations, all the Torah scrolls are removed from the Ark and the bimah ("pulpit") is circled seven times (hakkafot). All the men present are called to the Torah reading (aliyyot); for this purpose, Deuteronomy 33:1–29 is repeated as many times as necessary. All the children under the age of bar mitzvah are called for the concluding portion of the chapter; this aliyah is referred to as kol ha-ne'arim ("all the youngsters"). A tallit is spread above the heads of the youngsters, and the congregation blesses them with Jacob's benediction to

Ephraim and Manasseh (Gen. 48:16). Those who are honored with the aliyyot which conclude and start the Torah readings are popularly designated as the hatan Torah and hatan Bereshit; they often pledge contributions to the synagogue and sponsor banquets for their acquaintances in honor of the event (see Bridegrooms of the Law). In many communities similar ceremonies are held on Simhat Torah eve: all the scrolls are removed from the Ark and the bimah is circled seven times. Some communities even read from the concluding portion of Deuteronomy during the evening service, the only time during the year when the Torah scroll is read at night (Sh. Ar., OH 669:1).

The Simhat Torah festivities are accompanied by the recitation of special liturgical compositions, some of which were written in the late geonic period. The hatan Torah is called up by the prayer Me-Reshut ha-El ha-Gadol, and the hatan Bereshit by Me-Reshut Meromam. The return of the Torah scrolls to the Ark is accompanied by the joyful hymns "Sisu ve-Simhu be-Simhat Torah" and "Hitkabbezu Malakhim Zeh el Zeh." A central role in the festivities is allotted to children. In addition to the aliyah to the Torah, the children also participate in the Torah processions: they carry flags adorned with apples in which burning candles are placed. There have even been communities where children dismantled sukkot on Simhat Torah and burned them (Darkhei Moshe to OH 669 n. 3 quoting Maharil).

Hasidim also hold Torah processions on Shemini Azeret eve. Reform synagogues observe these customs, in a modified form, on Shemini Azeret, which is observed as the final festival day. In Israel, where the second day of the festival is not celebrated, the liturgy and celebration of both days are combined. It has also become customary, there, for public hakkafot to be held on the night following Simhat Torah, which coincides with its celebration in the Diaspora: in many cities, communities, and army bases, seven hakkafot are held with religious, military, and political personnel being honored with the carrying of the Torah scrolls.

[Aaron Rothkoff]

In the U.S.S.R

Among Soviet Jewish youth seeking forms of expressing their Jewish identification, Simhat Torah gradually became, during the 1960s, the occasion of mass gatherings in and around the synagogues, mainly in the great cities Moscow, Leningrad, Riga, and others. At these gatherings large groups of Jewish youth, many of them students, sang Hebrew and Yiddish songs, danced the hora, congregated and discussed the latest events in Israel, etc. In the beginning, the Soviet authorities tried to disperse these "unauthorized meetings," but when Jewish and Western public opinion began to follow them and press correspondents as well as observers from various foreign embassies began attending them, the authorities largely reverted their attitude and even instructed the militia to cordon off the synagogue areas and redirect traffic, so as not to cause clashes with the Jewish youngsters, whose numbers swelled rapidly in Moscow into the tens of thousands. In many cities in the West, notably in Israel, England, the United States, and Canada, Simhat Torah was declared by Jewish youth as the day of "solidarity with Soviet Jewish youth," and mass demonstrations were staged voicing demands to the Soviet authorities for freedom of Jewish life and the right of migration to Israel.

[Editorial Staff Encyclopaedia Judaica]

Talmud Megillah 31a:

THE SECTION OF BLESSINGS AND CURSES.1 THE SECTION OF CURSES MUST NOT BE BROKEN UP, BUT MUST ALL BE READ BY ONE PERSON. ON MONDAY AND THURSDAY AND ON SABBATH AT MINHAH THE REGULAR PORTION OF THE WEEK IS READ, AND THIS IS NOT RECKONED AS PART OF THE READING [FOR THE SUCCEEDING SABBATH],2 AS IT SAYS,3 AND MOSES DECLARED UNTO THE CHILDREN OF ISRAEL. THE APPOINTED SEASONS OF THE LORD;'4 WHICH IMPLIES THAT IT IS PART OF THEIR ORDINANCE THAT EACH SHOULD BE READ IN ITS SEASON.

GEMARA. Our Rabbis taught: 'On Passover we read from the section of the festivals5 and for haftarah the account of the Passover of Gilgal'.6 Now7 that we keep two days Passover, the haftarah of the first day is the account of the Passover in Gilgal and of the second day that of the Passover of Josiah.8 'On the other days of the Passover the various passages in the Torah relating to Passover are read'9 What are these? — R. Papa said: The mnemonic is M'A'P'U'.10 'On the last day of Passover we read, And it came to pass when God sent,11 and as haftarah, And David spoke'.12 On the next day we read, All the firstborn,13 and for haftarah, This very day.14 Abaye said: Nowadays the communities are accustomed to read 'Draw the ox', 'Sanctify with money', 'Hew in the wilderness', and 'Send the firstborn'.15 'On Pentecost, we read Seven weeks,16 and for haftarah a chapter from Habakuk.17 According to others, we read In the third month,18 and for haftarah the account of the Divine Chariot'.19 Nowadays that we keep two days, we follow both courses, but in the reverse order.20 On New Year we read On the seventh month,21 and for haftarah, Is Ephraim a darling son unto me.'22 According to others, we read And the Lord remembered Sarah23 and for haftarah the story of Hannah.24 Nowadays that we keep two days, on the first day we follow the ruling of the other authority, and on the next day we say, And God tried Abraham,25 with 'Is Ephraim a darling son to me' for haftarah. On the Day of Atonement we read After the death26 and for haftarah,For thus saith the high and lofty one.27 At minhah we read the section of forbidden marriages28 and for haftarah the book of Jonah.29

R. Johanan said:30 Wherever you find [mentioned in the Scriptures] the power of the Holy One, blessed be He, you also find his gentleness mentioned. This fact is stated in the Torah, repeated In the Prophets, and stated a third time in the [Sacred] Writings. It is written in the Torah, For the Lord your God, he is the God of gods and Lord of lords,31 and it says immediately afterwards, He doth execute justice for the fatherless and widow. It is repeated in the Prophets: For thus saith the High and Lofty One, that inhabiteth eternity whose name is holy,32 and it says immediately afterwards, [I dwell] with him that is of a contrite and humble spirit. It is stated a third time in the [Sacred] Writings, as it is written: Extol him that rideth upon the skies, whose name is the Lord,33 and immediately afterwards it is written, A father of the fatherless and a judge of the widows.

'On34 the first day of Tabernacles we read the section of the festivals in Leviticus, and for haftarah, Behold a day cometh for the Lord'.35 Nowadays that we keep two days, on the next day we read the same Section from the Torah, but what do we read for haftarah.? — And all the men of Israel assembled unto King Solomon.36 On the other days of the festival we read the section of the offerings of the festival.37 On the last festival day we read, 'All the firstlings', with the commandments and statutes [which precede it],38 and for haftarah, 'And it was so that when Solomon had made an end'.39 On the next day we read, 'And this is the blessing',40 and for haftarah, 'And Solomon stood'.41

R. Huna said in the name of R. Shesheth: On the Sabbath which falls in the intermediate days of the festival, whether Passover or Tabernacles, the passage we read from the Torah is 'See, Thou [sayest unto me]'42 and for haftarah on Passover the passage of the 'dry bones',43 and on Tabernacles, 'In that day when Gog shall come'.44 On Hanukkah we read the section of the Princes45 and for haftarah [on Sabbath] that of the lights in Zechariah.46 Should there fall two Sabbaths in Hanukkah, on the first we read [for haftarah] the passage of the lights in Zechariah and on the second that of the lights of Solomon.47 On Purim we read 'And Amalek came'.48 On New Moon, 'On your new moons'.49 If New Moon falls on a Sabbath, the haftarah is [the passage concluding] 'And it shall come to pass that from one new moon to another'.50 If it falls on a Sunday, on the day before the haftarah is, 'And Jonathan said to him, tomorrow is the new moon'.51 R. Huna said:

____________________

(1) Lev. XXVI.

(2) And must be repeated on the Sabbath.

(3) This refers to all the previous part of the Mishnah.

(4) Lev. XXIII, 44.

(5) Lev. XXIII.

(6) Josh. V.

(7) This is an interpolation in the Baraitha inserted by an Amora who lived In Babylon and gives the practice of the Galuth.

(8) II Kings XXIII.

(9) Lit., 'he collects and reads of the subject of the day'.

(10) M=mishku (Draw and take you lambs, Ex. XII, 21); A=im ( If thou lend money to any of my people, Ibid. XXII, 24); P = pesol (Hew thee two tables of stone, Ex. XXXIV, 1); U = wayedaber (And God spoke, Num. IX, 1). All these passages go on to speak of Passover.

(11) Ex. XII, 17 relating to the passage of the Red Sea which is supposed to have taken place on the seventh day.

(12) David's song of deliverance in II Sam. XXII.

(13) Deut. XV, 19.

(14) Isa. X, 32 referring to the overthrow of Sennacherib which is supposed to have taken place on Passover.

(15) A mnemonic of the key words in the passages following the order: Ex. Xli, 21; Lev. XXII, 27; Ex. XIII; Ex. XXII, 24; Ex. XXXIV, 1; Num. IX, I; Ex. XIII, 17; Deut. XV, 19. Cf. Tosaf.

(16) Deut. XVI, 9.

(17) Hab. III, which describes the giving of the Law, commemorated (according to the Rabbis) by Pentecost.

(18) Ex. XIX.

(19) Ezek. I, describing the heavenly hosts who also are supposed to have appeared on Mount Sinai.

(20) I.e., Ex. XIX on the first day.

(21) Num. XXIX, 1.

(22) Jer. XXXI, 20. The text proceeds, 'For I shall surely remember him', which is suitable to the day of memorial.

(23) Gen. XXI, in order that the merit of Isaac may be remembered.

(24) l Sam. I, because Hannah was supposed to have been visited on New Year.

(25) Gen. XXII.

(26) Lev. XVI.

(27) Isa. LVII, 15, which goes on to speak of repentance.

(28) Lev. XVIII. Apparently this section is chosen because the temptation to sexual offences is particularly strong (Rashi). Cf. Tosaf.

(29) Which speaks of repentance.

(30) The reference to Isa. LVII leads to the introduction of the passage which follows.

(31) Deut. X, 17.

(32) Isa. LVII, 15.

(33) Ps. LXVIII, 5.

(34) The Barait

Ludwig Nadelman

Published by Unknown.

I was surfing the web, and came across this obituary from the NY Times for Ludwig Nadelman, so I decided to put it on the blog to record some of the history of the congregation for posterity.

LUDWIG NADELMAN

New York Times

Published: December 8, 1986

Rabbi Ludwig Nadelman, a leading figure in the Jewish Reconstructionist movement, died Saturday at White Plains Hospital. He was 58 years old and lived in Scarsdale, N.Y.

Rabbi Nadelman was executive vice president and then president of the Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation from 1973 to 1982.

He was also a leading member of the Rabbinical Assembly, a national organization of Conservative rabbis.

Reconstructionism is based on the idea that Judaism is an evolving civilization rather than only a faith. It places strong emphasis on Zionism.

Rabbi Nadelman was born in Berlin in 1928. His mother and grandparents later fled with him to Ecuador to escape Nazi rule. He came to New York in 1946 and graduated from Yeshiva University.

Rabbi Nadelman was the spiritual leader of the M'vakshe Derekh congregation in Westchester County. He founded the congregation in 1982.

He is survived by his wife, Judith; three sons: Ethan, of Cambridge, Mass.; Jeremy, of the Bronx, and Daniel, of Washington, and a daughter, Deborah, of Baltimore.

Afternoon Discussion group (Texts)

Published Sunday, October 01, 2006 by Unknown.The Yom Kippur Discussion Group for 5767 will meet on Monday at 4pm

Ben Newman will be leading a discussion of the following texts (and songs). Read them in advance, and come ready with comments...

1) Pitchu li sh’arei tzedek avo vam odeh yah (2x), zeh ha-sha’ar la-donai tzaddikim yavo’u vo (2x)

פתחו לי שערי צדק אבא בם אודה יה, זה השער ליי' צדיקים יבאו בו

2) Im nin’alu daletei nedivim, daletei marom lo nin’alu (2x), El Chai meromam me-al keruvim kulam be-rucho ya’alu (2x), chayot she-hen ratzo va-shovim mi-yom beriah nichlelu (2x)

אם נינעלו דלתי נדיבים דלתי מרום לא נינעלו, אל חי מרומם מעל כרובים כולם ברוחו יעלו, חיות שהן רצוא ושובים מיום בריאה נכללו

Texts:

זוהר ויקרא חלק ג דף סט ע"א-ב :

תנינן בשעתא דברא קב"ה עלמא למברי בר נש אמליך באורייתא אמרה קמיה תבעי למברי האי בר נש זמין הוא למחטי קמך. זמין הוא לארגזא קמך אי תעביד ליה כעובדוי הא עלמא לא יכיל למיקם קמך כ"ש ההוא בר נש א"ל וכי למגנא אתקרינא (שמות לד) קל רחום וחנון ארך אפים. ועד לא ברא קב"ה עלמא ברא תשובה אמר לה לתשובה אנא בעינא למברי בר נש בעלמא על מנת דכד יתובון לך מחוביהון דתהוי זמינא למשבק חוביהון ולכפרא עלייהו. ובכל שעתא ושעתא תשובה זמינא לגבי בני נשא וכד בני נשא תייבין מחובייהו האי תשובה תבת לגבי קב"ה וכפר על כלא ודינין אתכפיין ומתבסמאן כלהו ובר נש אתדכי מחוביה. אימתי אתדכי בר נש מחוביה בשעתא דעאל בהאי תשובה כדקא חזי...

Zohar Vayikra Section 3, 69a-b:

“We have learnt", he said, “that when God was about to create man, He consulted the Torah and she warned Him that he would sin before Him and provoke Him. Therefore, before creating the world God created Repentance, saying to her: ’I am about to create man, on condition that when they return to thee from their sins thou shalt be prepared to forgive their sins and make atonement for them.’” Hence at all times Repentance is close at hand to men, and when they repent of their sins it returns to God and makes atonement for all, and judgement is suppressed and all is put right. When is a man purified of his sin? R. Isaac said: "When he returns to the Most High King and prays from the depths of his heart, as it is written, ’From the depths I cried unto thee’." R. Abba said: "There is a hidden place above, which is ’the depth of the well’whence issue streams and sources in all directions. This profound depth is called Repentance, and he who desires to repent and to be purified of his sin should call upon God from this depth. We have learnt that when a man repented before his Master and brought his offering on the altar, and the priest made atonement for him and prayed for him, mercy was aroused and judgement mitigated and Repentance poured blessings on the issuing streams and all the lamps were blessed together, and the man was purified from his sin.”

רמב"ם משנה תורה הלכות תשובה ב"

(א) אי זו היא תשובה גמורה זה שבא לידו דבר שעבר בו ואפשר בידו לעשותו ופירש ולא עשה מפני התשובה לא מיראה ולא מכשלון כח כיצד הרי שבא על אשה בעבירה ולאחר זמן נתייחד עמה והוא עומד באהבתו בה ובכח גופו ובמדינה שעבר בה ופירש ולא עבר זהו בעל תשובה גמורה הוא ששלמה אמר וזכור את בוראיך בימי בחורותיך ואם לא שב אלא בימי זקנותו ובעת שאי אפשר לו לעשות מה שהיה עושה אף על פי שאינה תשובה מעולה מועלת היא לו ובעל תשובה הוא אפילו עבר כל ימיו ועשה תשובה ביום מיתתו ומת בתשובתו כל עונותיו נמחלין שנאמר עד אשר לא תחשך השמש והאור והירח והכוכבים ושבו העבים אחר הגשם שהוא יום המיתה מכלל שאם זכר בוראו ושב קודם שימות נסלח לו:

1) Repentance is completed when an opportunity to commit one's original transgression again arises but one doesn't and repents instead, but not if the reason for repenting was that someone was watching or because of physical weakness. For example, if one copulated in sin with one's wife, and then later one had another opportunity to do it again but didn't, then even though one may still love her and she may be in perfect physical health and was even in the same country [when the opportunity arose], one has repented completely. Solomon said, "Remember now your Creator in the days of your youth, before the evil days come, and the years draw near when you shall say, `I have no pleasure in them'". If one repented only one's old age, or at a time when one can no longer commit the original sin, then it is not the best type of repentance, but it is to his advantage and is nevertheless repentance. Even if one sinned throughout one's life but repented on one's dying day and died atoned, then all one's sins are forgiven, as it is written,"...before the sun, or the light, or the moon, or the stars are darkened, and the clouds return after the rain", which refers to the day of one's death. The general rule is that one is forgiven provided one repented before dying.

From the Tractate Yoma, pp. 85a-85b (Trans. from Emanuel Levinas, Nine Talmudic Readings) :

Mishna: The transgressions of man toward God are forgiven him by the Day of Atonement; the transgressions against other peo¬ple are not forgiven him by the Day of Atonement if he has not first appeased the other person.

Gemara: Rabbi Joseph bar Helbe put the following objection to Rabbi Abbahu: How can one hold that faults committed by a man against another are not forgiven by the Day of Atonement when it is written (1 Samuel 2): "If a man offends another man, Elohim will reconcile." What does Elohim mean? The judge. If that is so, then read the end of the verse: "If it is God himself that he offends, who will intercede for him?" Here is how it should be understood: If a man commits a fault toward another man and appeases him, God will for¬give; but if the fault concerns God, who will be able to intercede for him? Only repentance and good deeds.

Rabbi Isaac has said: "Whoever hurts his neighbor, even through words, must appease him (to be forgiven), for it has been said (Proverbs 6:1-3) "My son, if you have vouched for your neighbor, if you have pledged your word on behalf of a stranger, you are trapped by your promises; you have become the prisoner of your word. Do the following, then, my son, to regain your freedom, since you have fallen into the other's power: go, insist energetically and mount an assault upon your neighbor (or neighbors)." And the Gemara adds its in¬terpretation of the last sentence: If you have money, open a generous hand to him, if not assail him with friends.

... Rab Yose bar Hanina has said: Whoever asks of his neighbor to release him should not solicit this of him more than three times, for it has been said (when, after the death of Jacob, Joseph's brothers beg for forgiveness): "Oh, for mercy's sake, forgive the injury of thy brothers and their fault and the evil they did you. Therefore forgive now the servants of the God of your father their wrongs" (Genesis 50:17).

. . . Rab once had an altercation with a slaughterer of live¬stock. The latter did not come to him on the eve of Yom Kippur. He then said: I will go to him myself to appease him. (On the way) Rab Huna ran across him. He said to him: Where is the master going? He answered: To reconcile with so and so. Then, he said: Abba is going to commit murder. He went anyway. The slaughterer was seated, hammering an ox head. He raised his eyes and saw him. He said to him: Go away, Abba. I have nothing in common with you. As he was hammering the head, a bone broke loose, lodged itself in his throat, and killed him.

Rab was commenting upon a text before Rabbi. When Rab Hiyya came in, he started his reading from the beginning again. Bar Kappara came in-he began again; Rab Simeon, the son of Rabbi, came in, and Rab again went back to the beginning. Then Rab Hanina bar Hama came in, and Rab said: How many times am I to repeat myself? He did not go back to the beginning. Rab Hanina was wounded by it. For thirteen years, on Yom Kippur eve, Rab went to seek forgive¬ness, and Rav Hanina refused to be appeased.

But how could Rab have proceeded in this manner? Did not Rab Yose bar Hanina say: Whoever asks of his neighbor to release him must not ask him more than three times? Rab, that is altogether different.

And why did Rabbi Hanina act this way? Didn't Raba teach: One forgives all sins of whoever cedes his right? The reason is that Rabbi Hanina had a dream in which Rab was hanging from a palm tree. It is said: "Whoever appears in a dream, hanging from a palm tree, is destined ,for sover¬eignty." He concluded from it that Rab would be head of the academy. That is why he did not let himself be appeased, so that Rab would leave and teach in Babylon.

An Excerpt from Levinas’ Commentary:

Let us evaluate the tremendous portent of what we have just learned My faults toward God are forgiven without my depending on his good will God is, in a sense, the other, par excellence, the other as other, the absolutely other-and nonetheless my standing with this God depends only on myself. The instrument of forgiveness is in my hands. On the other hand my neighbor, my brother, man, infinitely less other than the absolutely other, is in a certain way more other than God: to obtain his forgiveness on the Day of Atonement I must first succeed in appeasing him. What if he refuses? As soon as two are involved, everything is in danger. The other can refuse forgiveness and leave me forever unpardoned. This must hide some interesting teachings on the essence of the Divine!

How are the transgressions against God and the transgressions against man distinguished? On the face of it, nothing is simpler than this distinc¬tion: anything that can harm my neighbor either materially or morally, as well as any verbal offense committed against him, constitutes a transgres¬sion against man. Transgressions of prohibitions and ritual commandments, idolatry and despair, belong to the realm of wrongs done to the Eternal. Not to honor the Sabbath and the laws concerning food, not to believe in the triumph of the good, not to place anything above money or even art, would be considered offenses against God. These then are the faults wiped out by the Day of Atonement as a result of a simple contrition and peniten¬tial rites. It is well understood that faults toward one's neighbor are ipso facto offenses toward God.

One could no doubt stop here. It could be concluded a bit hastily that Judaism values social morality above ritual practices. But the order could also be reversed. The fact that forgiveness for ritual offenses depends only on penitence-and consequently only on us-may project a new light on the meaning of ritual practices. Not to depend on the other to be forgiven is certainly, in one sense, to be sure of the outcome of one's case. But does calling these ritual transgressions "transgressions against God" diminish the gravity of the illness that the Soul has contracted as a result of these transgressions?

Perhaps the ills that must heal inside the Soul without the help of others are precisely the most profound ills, and that even where our social faults are concerned, once our neighbor has been appeased, the most diffi¬cult part remains to be done. In doing wrong toward God, have we not undermined the moral conscience as moral conscience? The ritual transgres¬sion that I want to erase without resorting to the help of others would be precisely the one that demands all my personality; it is the work of Teshuvah, of Return, for which no one can take my place.

To be before God would be equivalent then to this total mobilization of oneself. Ritual transgression-and that which is an offense against God :n the offense against my neighbor-would destroy me more utterly than the offense against others. But taken by itself and separated from the im¬piety it contains, the ritual transgression is the source of my cruelty, my harmfulness, my self-indulgences. That an evil requires a healing of the self by the self measures the depth of the injury. The effort the moral conscience makes to reestablish itself as moral conscience, Teshuvah, or Return, is simultaneously the relation with God and an absolutely inter¬nal event.

There would thus not be a deeper interiorization of the notion of God than that found in the Mishna stating that my faults toward the Eternal are iorgiven me by the Day of Atonement. In my most severe isolation, I obtain forgiveness. But now we can understand why Yom Kippur is needed in or¬der to obtain this forgiveness. How do you expect a moral conscience af¬fected to its marrow to find in itself the necessary support to begin this progress toward its own interiority and toward solitude? One must rely on the objective order of the community to obtain this intimacy of deliverance. A set day in the calendar and all the ceremonial of solemnity of Yom Kippur are needed for the "damaged" moral conscience to reach its intimacy and reconquer the integrity that no one can reconquer for it. This is the work that is equivalent to God's pardon. This dialectic of the collective and the intimate seems very important to us. The Gemara even preserves an ex¬treme opinion, that of Rabbi Judah Hanassi, who attributes to the day of Yom Kippur itself-without Teshuvah-the power to purify guilty souls, so important within Jewish thought is the communal basis of inner rebirth. Perhaps this gives us a general clue as to the meaning of the Jewish ritual and of the ritual aspect of social morality itself. Originating communally, in collective law and commandment, ritual is not at all external to conscience. It conditions it and permits it to enter into itself and to stay awake. It pre¬serves it, prepares its healing. Are we to think that the sense of justice dwelling in the Jewish conscience-that wonder of wonders-is due to the fact that for centuries Jews fasted on Yom Kippur, observed the Sabbath and the food prohibitions, waited for the Messiah, and understood the love of one's neighbor as a duty of piety?...

Stories from the Ethical Kabbalah:

The Anonymous Penitent

The virtue of anonymity in repentance.

In the days of the Ari-may his memory be for a blessing for the life of the world to come-there was one man, a penitent, who from time to time would go to the synagogue after midnight clad from head to toe in sackcloth so that people might not recognize him. And he would turn his face toward the wall,' standing there half the night' and all the following day until midnight, praying, pleading, and weeping. Only after midnight when everyone was asleep would he leave the synagogue to go home, and absolutely no one knew who he was.

The Rabbi (the Ari) used to say that this certainly exemplifies complete and perfect repentance.' For repentance and almsgiving are on the same level: Just as almsgiving is most perfect when done in secret, so is repentance when it is done in a clandestine manner. And such secrecy is beneficial in that the other side is unable to prevail over the penitent to make him depart from the ways of repentance.

Hemdat yamim, Yamim noraim 48b

The Ari and the Penitent

A man guilty of a grave sin is prepared to die as his way of atonement. His very readiness to die atones for his past.

In the days of the Rabbi (the Ari)-may his memory be for a blessing for the life of the world to come-it happened that a rich person came to him with the purpose of testing his knowledge. The Rabbi told him that he had seven abominations in his heart and disclosed to him all the details of the transgressions that he had committed. The Rabbi also told the wealthy man that he had had sexual relations with his maid. The man acknowledged all his transgressions without embarrassment, denying only his having had intimate relations with his maid. This he would not acknowledge until the Rabbi told him, "Now you will see me produce that accursed one in your presence." And the Rabbi placed his hands upon that man and produced the maid's image and likeness, a harlot and a scoundrel, and the man recognized her and declared, "She is more righteous than I"

His soul almost departed as he fell at the Rabbi's feet saying, "I have sinned and have clearly transgressed." And the Rabbi-may he rest in peace-restored his soul to him. Then the man cried with a bitter voice, crying and pleading before the Rabbi, "Just remove this death from me!" He answered, "This is yours in order that you will know that the sages said in truth that one who has [illicit] intimate relations with a non-Jewish woman will be bound with her like a dog even in the world to come.' She is bound to you and will depart only with great repentance and acts of rectification." The man responded, "Behold, I am prepared to accept even the four deaths imposed by the court." Then the Rabbi answered him, "Your penance is through burning."

As the man heard this, he took out money from his pocket to purchase wood with which to burn himself. The Rabbi told him that his judgment was not like that of the other nations, for according to Jewish law it was necessary to throw a boiling lead wick into the mouth.' And the man answered, "Whatever happens, I shall die." The Rabbi then ordered that lead be purchased, and they brought it and placed it upon the fire. The Rabbi told him to recite the confession [viddui] of one dangerously ill. And he did so.

He told him, "Throw yourself to the ground." And he lay down on the ground. He said to him, "Stretch out your hands." And he stretched them out. "Close your eyes." And he closed them. "Open your mouth." And he opened it. The Rabbi immediately threw into his mouth various kinds of sweets that he had on hand for the occasion and said to him, "Your iniquity is removed and your sin is atoned. The Lord has removed your sin. You shall not die."

And the Rabbi raised him from the ground and wrote for him acts of tikkun for his soul. As part of the acts of penance he commanded him to read each day five pages from the Zohar, even though the man told him that the Lord had withheld this wisdom from him and that he was totally unfamiliar with it. Nevertheless he commanded him to read, even without understanding, in order to mend his soul. And that man died in a state of complete repentance. (Hemdat yamim, Yamim noraim 5b-6a)

Baal Shem Tov Stories:

Your Own Sins

BAAL SHEM TOV WAS ONCE IN A CERTAIN TOWN WHERE HE MET A PREACHER who was constantly inveighing against the evil inclination that leads people to the gates of hell. "Tell me," the Besht asked him, "how do you know so much about the ways of the evil inclination, when you've never committed any sins of your own?" The preacher was puzzled. "How do you know that I haven't sinned?" "My friend," said the Besht, "if you have sinned, then first rebuke yourself. Don't go on making a long list of other people's sins."'

The Stolen Harness

THE BAAL SHEM TOV WAS ONCE ABOUT TO BEGIN A JOURNEY, BUT SINCE IT / was the evening for blessing the new moon, he delayed his departure from Medzibuz until nighttime. He told his attendant to have the horses harnessed to the coach and ready to travel, so that he could leave as soon as he returned from the syna¬gogue. The attendant did as he was told, getting the horses' equipment, harnessing the horses to the coach, and bringing the coach out to the front of the house.

Then, the Baal Shem Tov, accompanied by one of his disciples, left his house to go recite the new moon blessing with the congregation. As they began walking down the street, the disciple wanted to turn around to look back, but the Besht told him not to, saying, "Don't look. Someone is stealing the harness from the horses." The disciple was surprised at the Besht's words and even more surprised at his explanation, which followed. "He's stealing because he needs money for Sabbath expenses." So they went on to the synagogue and out in front of the synagogue, on the street, they blessed the new moon with the congregation.

When they were walking back and nearing the house, the Besht's attendant had just discovered that the harness was missing and began to shout, "Who stole the harness?" But the Besht hushed him, saying, "Don't shout! The thief pawned it with a certain person. Take this money"-he handed him a specific sum-"and go to him and redeem it. And don't publicize the matter."

The holy Baal Shem Tov judged the thief favorably, for good-that he was stealing for his Sabbath expenses. Later that day, the Besht reached the town to which he was traveling. And between Minha and Maariv he taught his disciples there about judging others favorably. He said, "I once made a soul-ascent and saw the angel Michael, the great heavenly intercessor for Israel, defending the Jewish people by arguing that all their vices in money matters, such as cheating in business, were really virtues, because

all their lowly acts were done in order to be able to serve God-to have money to make a shidduch (marriage-connection) with a Torah scholar or to give tzedaka and so on. From Michael," said the Besht, "I learned how to defend the Jewish people before the heavenly court."

"Earlier today in Medzibuz, I saw a thief stealing something from me. I didn't try to stop him and told myself that he was stealing for his Sabbath expenses. It might seem farfetched to say that the thief was stealing, so to speak, for the honor of the Sabbath. But why did God-who created everything for a purpose-give us the ability to be illogical? The answer is: So we could justify the faults of others. Most of us twist logic to justify our own behavior, but we should actually use our irrationality only to justify others.

"Never speak ill of any Jew, or when the Satan accuses him, he'll call you to be his witness. When the Satan accuses a Jew before the Throne of Glory, his single accusa¬tion is not accepted as true, because the Torah says: `According to two witnesses shall the matter be established.' Therefore, the Satan waits until he can find a partner to defame the person. If you have to mention a particular person when condemning some bad trait, say explicitly that you're not talking about the person himself, but just about his bad trait.

Arousing an Accusation Above

1( DURING THE PRAYERS ONE ROSH HASHANAH, THE SNUFF BOX OF ONE OF the Baal Shem Tov's disciples fell to the ground, whereupon he picked it up and sniffed the tobacco. This disciple, like some others at that time, used snuff to keep alert and increase his concentration while praying. But another disciple was annoyed at seeing this and thought, "How can he interrupt in the middle of the prayers and sniff tobacco?" This tzaddik's annoyance aroused an accusation in heaven and caused a heavenly decree that the man he criticized die that year.

The Besht saw all this with his holy spirit and made a soul-ascent to defend the accused before the heavenly court, "How can a punishment of death be decreed for such a minor transgression?" But none of his arguments succeeded and he could not cause the decree to be annulled. As a result, the Besht was upset and troubled.

On Hoshanna Rabba*, he made another soul-ascent, and he argued and complained and cried out, until he achieved by his prayer that if the accuser himself found a justifi¬cation for his comrade, the decree would be ripped up and the other disciple par¬doned. The Besht then entered his belt midrash, and found the accusing disciple sitting reciting the Hoshanna Rabba Tikkun. By mystical means, the Baal Shem Tov removed the disciple's power of concentration so that he could no longer recite the tikkun with d'vekut! He then got up and began to walk around thinking about various matters, such as, "Why did divine providence arrange for snuff and smoking tobacco to be introduced into Europe in recent generations?" It occurred to him that certain souls were only able to meditate and concentrate with the help of tobacco. When he thought this, he regretted having been critical of his fellow disciple, who had been sniffing tobacco while praying.